Note: This article was inspired by Neal over at SaxStation who published this post about 12-key practice.

I’m sure we’ve all heard the legends about Bird practicing all tunes in every key at any tempo. And regardless whether this is true or not (which I’m sure is to some degree…I doubt he played “Donna Lee” in every key for example, but I bet he moved “Indiana” around), it sure sets a high bar for fluent modern Jazz musicians.

So why would anyone do such a thing? Can’t we just agree on common key centers, like always having “Cherokee” in Bb and “Days of Wine & Roses” in F?

How I Used to Learn Tunes

For many (if not all) of my students and definitely for me, I learned tunes by figuring out the notes, getting comfortable with the head, the chords…etc. I’d improvise bass lines to acclimate to the roots, play guide tones to study the inner voices and possible routes through the chords and arpeggiate and invert all the harmonies. I’d also reference as many recordings as I could (especially by great ’30s to ’60s players, since modern guys are notorious for elaborating, reharmonizing and otherwise distorting).

What was the result? I’d usually know the tune pretty well in the key of “[key-my-lead-sheet-was-in]”, and in time and with study could hear its function and form consistently. Success, right? Well…partly…

Learning On the Gig

This last weekend, I had the pleasure of playing with two very gifted musicians – Bob Lashier on Bass, and Peter Zale on piano, both of whom are tremendously well versed in playing in any key. And any key is fair game – easy ones like “Blue Monk” in C and “Someday My Prince Will Come” in F (or in E Bob!!!), and more sophisticated ones like “It Could Happen to You” in G and “Autumn Leaves” wherever they felt like putting it that night.

You see, they frequently back singers. And like all musicians, singers have limitations based on their “instrument”. Range considerations tend to matter a great deal, and can very often make the difference in a successful performance…too high and your singer sounds like a screeching banshee. Too low and that sultry voice now sounds like a crooning thug from Brooklyn. As accompanists (and yes Mr. Future-Sax-Revolutionary, you are an accompanist in this situation) we have to make sure everyone sounds their best, and “Days” in F may be an awful key for the singer, but A might suit them nicely.

I am by no means a master at this, but the work I’ve done has given me enough skill to face these situations head on and usually come out with only a few bruises. And since the singer is often the bandleader, or has the ear of the leader after the show, making them comfortable sure helps job security.

So does this justify all that work? Not so much? Maybe you don’t work with singers, or they do tunes in your keys.

How Practicing In 12 Keys Changes Your Thinking

If you take lessons with Jerry Bergonzi, your learning curve goes vertical. He threw a huge variety of challenges at me. On my very first lesson, when I was still star-stricken, Jerry assigned me a project that I haven’t let up on yet. The challenge? Memorize 5 tunes every 2 weeks (that’s how often we had lessons), one of which I should be learned in all 12 keys. He suggested I start with “Have You Met Miss Jones”. Ouch…that bridge…

That was a tall order. Sometimes I’d get close…usually the 5th tune would be foggy in my mind, but the others were doable. Other times, I’d get stuck on the 12-key tune and never get to the others. But I began to notice a huge change in my method for memorizing a tune.

I began to think numerically and functionally, rather than by letters.

Let me explain. We all know the progression Dmin7, G7, CΔ7, the ever-present ii-V7-I progression. A college professor once told me that this progression makes up about 3/4 of all jazz tunes out there…something I can’t imagine anyone has ever attempted to verify (I mean, how could you?), but I’m sure we can agree it occurs a lot.

The key to taking advantage of this is realizing that this is a ii-V7-I. Lets look at the bridge for “Have You Met Miss Jones”:

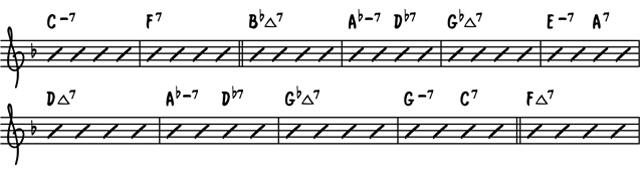

The Bridge (in the key of F, starting 2 bars early, ending a bar late):

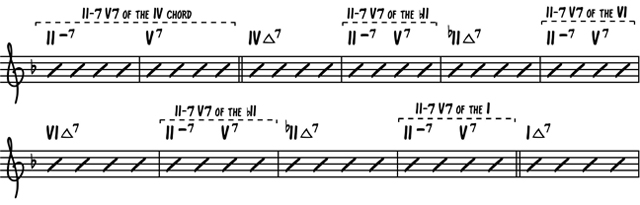

It’s a huge challenge if you try to retain every chord as a separate item. But realizing that you have a ii-V-I progression over two bars, over and over again in keys dropping by Major 3rds sure organizes things better.

Now, three chords merge into one common pattern. A mess of 12 chords gets reduced to a I chord and 3 ii-V-I progressions in 3 keys. If you count getting in and out of the bridge, it’s 15 chords cut down to 5 ii-V-Is in 4 keys. Not simple, but a heck of a lot better than it was before.

And the magic happens when you relocate the progression to a new key. Now I don’t have to move each chord in my mind by a specified interval. I just reconstruct it in the new key.

Closing Thoughts

I made an effort to reduce this concept to something simple, but this didn’t come to me easily. It took a great deal of effort and thought. So if it still seems complex, I guess it is to a degree.

But it was transformative in my thinking. Once I realized how much easier it was to relocate chords when you think in numbers, I stretched out to include more patterns…I-vi-ii-V, turnaround to ii, 12-bar Blues, V down progressions…and so on. This has hugely sped up my memorization process. What used to take weeks could now be hours if I can grasp the structure of a tune.

Are you convinced now? Maybe a bit overwhelmed?

This requires a good grasp of theory, and while it simplifies everything, you still have to be fluent in every key, and know these patterns in every key. This isn’t a magic bullet. But if you see a need to practice efficiently (and being a sax player with kids and too many jobs, I sure do) and you desire the flexibility this technique offers, don’t wait another moment.

The next time someone calls “My Romance” in D, you’ll be thankful you did.

Another note: Monica Shriver suggested I do a follow-up post describing my method for this. I agree…here it is…my method for practicing in all 12 keys.

Hey Adam,

Thanks for writing and giving a shout out to Sax Station.

I have played with singers before, and have gone to some keys other than usual. In that case, the ability to play in other keys is very helpful. And most singers don’t sing bebop (Lambert, Hendricks, Ross, Bavan, maybe Kurt Ellig being exceptions) which makes the process a bit easier. Your point about the ii V I pattern is a useful one. Recognizing patterns in songs is in an important step in strengthening your musicality I think (not just notes).

And thanks for sharing the stories about your lessons with Jerry Bergonzi. That’s cool you took lessons from him.

And the followup suggestion from Monica sounds good. I’ll second that!

-Neal

Pingback: Practicing Jazz In 12 Keys | Adam Roberts Music

Hey Adam,

Good stuff. I just wanted to add that I think Bird might very well have played Donna Lee in 12 keys, I have, and I spoke with cats from that time, Lou Donaldson and others, and playing heads in 12 keys was a big practice thing back then, and many of the schools around have the students play Donna Lee in 12 keys. Stitt historically practiced many tunes in 12 keys, and would just stomp off Body and Soul in the key of B if he was mad at his wife, or just wanted to knock everyone off the stage. I met Stitt once while in Pittsburgh, and I spoke with players who used to back him up.

Bird clearly had practiced for hours and hours, and so I thinks it’s possible or probable that he practiced Donna Lee in 12 keys, I know many other cats who have.

Cheers.

Marshall

And I wouldn’t deny it. You never know. I’ve only ever heard recordings of Bird playing his Bebop heads in the original (familiar?) keys, but with the practice regimen he’s renowned to have, there’d be plenty of time. I’m well aware of his descendants doing this though, so its logical.

Thanks for coming by!

Adam,

I am grateful for someone taking their time to explain common practical concepts, difficulties, and situations to young improvisers out there. Very nice read and I look forward to reading more about your solutions to problems as well as your general approach to improvisation.

Peace,

Mitch B.

Hey Adam,

Great post. In fact, I have noticed after many years of notn actually following the advice of so many books etc. on jazz: take this and then work it through all 12 keys. If you do then..At the beginning it’s a bastard, sure, but with time it gets easier…

Hey,

You are right.

1. learn to sing the Head

2. Play it On Sax

3. Play it in all Keys

3. Play changes in all keys (Root and quality)

This give you a complete new view on the tunes.

Ciao

How I did it is I picked a key and then played all my favorite songs in that key, as much as I could. I built an Android app for myself to help me pick keys at random. You can find it here: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.rockrussell.music.randomkey&hl=en

Enjoy.

while you are at it, practice scales too. It’ll pay off when you’re trying to improvise.

WTF???